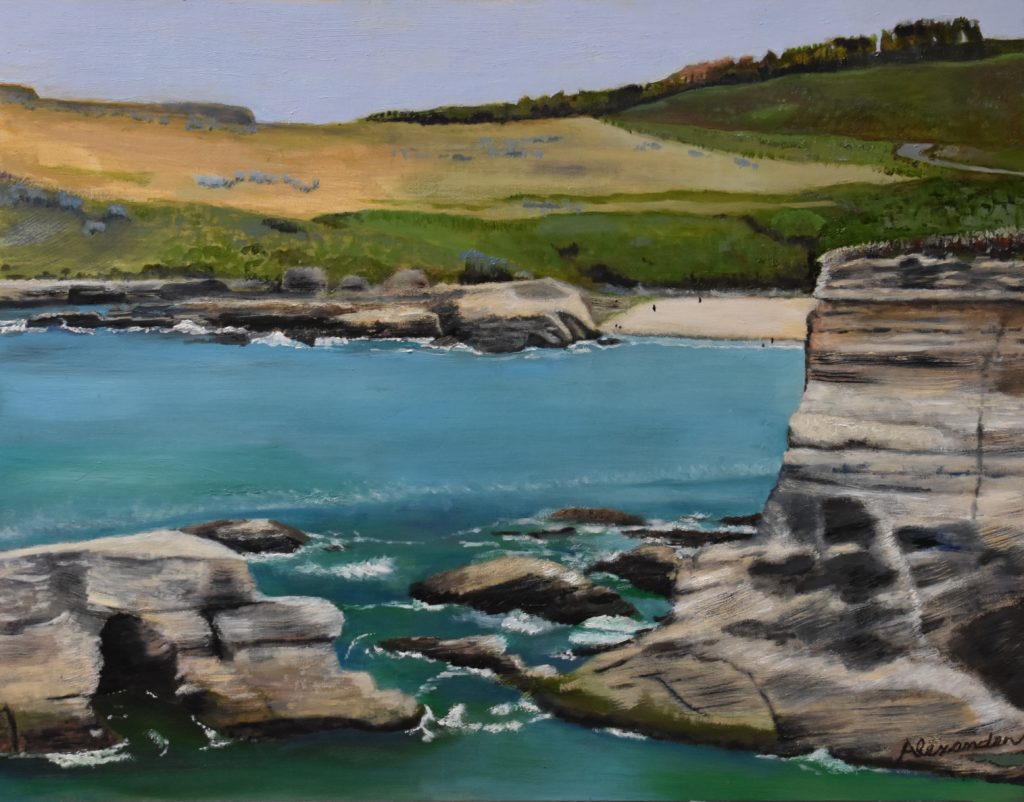

One stop on last month’s car trip to San Rafael, CA, was a visit with two couples I know in San Luis Obispo. I went plein air painting with Bridget Duffy on Monday and with Harvey Cohon on Tuesday. Mike hung out with the other spouse in each couple. What fun! The very next day, fires broke out and any further painting would have been out of the question. The air quality and visibility became poor.